Point of View

by Kathy Leonard Czepiel

There’s something to be said for repetition. Sepiessa Point, Marjorie Gillette Wolfe’s new photography exhibition, which shares the front area at Kehler Liddell Gallery with a group show featuring the collective’s newest members, is made up entirely of photographs taken in the Sepiessa Point Reservation on Martha’s Vineyard. Many of Wolfe’s photographs were taken at a 700-acre brackish body, Tisbury Great Pond, looking outward from its inland shore with the same delicate line of barrier beach on the horizon.

In the 20 years Wolfe has spent photographing the spot, familiarity has bred not contempt but appreciation. “I know I’m going to find Tisbury Great Pond, I know I’m going to see a barrier on the other side. I know that tree is going to be there,” the artist says, referring to a nearly trunkless tree with branches sprouting upward and outward like a mass of neurons. “But I’m telling you,” Wolfe adds, “every time there’s a surprise.”

This is a modest explanation that suggests the variety in Wolfe’s photographs comes from the chances provided by nature—the wind blowing here, the ice forming there, the blush of the sun in a hazy sky. But for viewers, many of the surprises in this exhibition come from Wolfe’s finely tuned sensitivity to shape and texture, light and color.

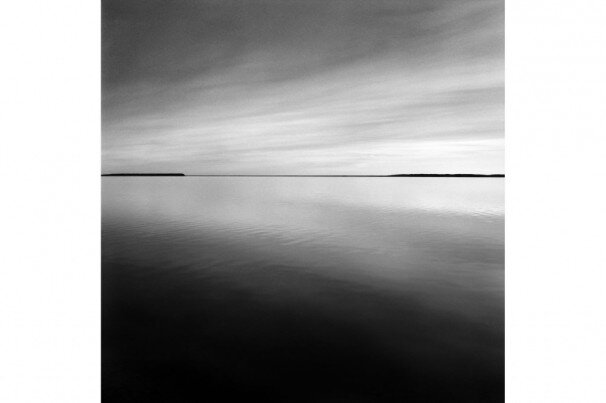

One series of five photographs literally offers the same view from the same spot, each one strikingly unique. Sepiessa Calm, in black and white, uses the dark pencil line of barrier beach to bisect the picture, separating water from sky. But both elements are subsumed by a cone of light that reaches across the image in stripes of white and gray—thinner in the sky, broader and rounded in the water. Sepiessa White, in subtle color, is a magnificent winter landscape in which blue tracks stripe the snow at water’s edge, providing a parallel to the frozen shoreline. Here, clouds like the spokes of a gigantic wheel are shot through with golden light, dissolving into a softened space somewhere between land and sky. The entire print shimmers like an old silver daguerreotype. Wolfe’s choices—color vs. black-and-white, how to handle the light, where to place the shoreline—add up to these striking, evocative images that make an argument for the vast range a single place can offer.

Even the way in which the photographs are arranged in the gallery demonstrates Wolfe’s artistic eye. A grouping in front plays on the clamshell curves of water and sand. In one image, a bow of sand rises toward the center of the photograph. In another, water bends toward the bottom of the frame. The repeated geometry establishes what we should be attuned to, so when we look at Sepiessa East Blue Sky, we see what we might otherwise have missed: a relaxed arc where wet sand meets dry, mirrored in the curving drift of steamy clouds and blue sky across the top of the color image.

Among this group themed with curves, Sepiessa White Horizon depends most on straight lines. Here, the dark line of horizon, slightly irregular due to the distant land formations edging the barrier beach, anchors the image. A smoke-colored sky bears down heavily like the lid of a cast iron pot. From the crack between them, bright light shoots forcefully toward the viewer. The lake’s water catches this light in its gentle ripples. But the picture’s most delightful element lies in the foreground. Here, wavelets break the horizontal theme, drifting sideways like creases in a wrinkled tablecloth.

Sepiessa Point includes several panoramic images and other gems: a photograph in which a patch of ice on the trail to the pond echoes the shape of a knobbly cloud arching across the sky; an image of that brainlike tree, its spidery branches echoed in the wispy tentacles of a cloud improbably perched like an ethereal jellyfish above; a shot of the sand that could be a moonscape.

Tisbury Great Pond is cleansed every few months when the barrier beach is cut to let the salt water in, Wolfe says, a practice that dates back hundreds of years to the Wampanoag, the pond’s original residents. “It’s better for the health of the fish and the shellfish. It’s just healthy for the pond,” she says. “The ocean comes in, cleans the pond, and the waves and the wind… bring the sand back in.” The process can take a day or two, or several months.

Nature will have its way. It will send remarkable clouds or a day so still that the pond could be a sheet of glass. It will send a winter so cold that salt water freezes. Luckily for us, Marjorie Gillette Wolfe was there to capture it and make it her own.